Dream Girl. The Sweet Voice of Reason

Opera News | by Brian Kellow

Joyce DiDonato — probably the most in-demand lyric-coloratura mezzo in the world — has become a star by playing up, not down, to her audiences. She tells BRIAN KELLOW how proud she is of opera — and how proud she is to be an opera singer.

Portrait photographed in New York by James Salzano Makeup and hair by Affan Malik / Clothes styled by Catherine Glazer / Gown by Carolina Herrera / Necklace by David Webb

On March 19, 2007, the Actors Fund of America and Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS presented the popular annual fund-raising concert “Nothin’ Like a Dame” at New York City’s Marquis Theater. A showcase for some of Broadway’s top women performers — past high points include Michele Lee singing “I’m Way Ahead,” from Seesaw, and Zoe Caldwell reciting the “old heads on young shoulders” speech from The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie — “Nothin’ Like a Dame” has traditionally made a place for one opera singer among the Broadway divas. This time around, the opera berth was filled by mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato. Instead of choosing a safe aria such as Carmen’s habanera, DiDonato did her audience the favor of trusting it. She walked onstage as if it were the most natural thing in the world for her to be there and launched into a stunning performance of La Cenerentola‘s “Non più mesta.” “On Broadway,” she later said, “they do that key change up when the emotion gets big. Rossini didn’t do that. He just keeps adding notes.” DiDonato didn’t play to the crowd; she sang with the same authority she had demonstrated on the world’s leading opera stages. The Broadway fans — often so quick to tell you that opera isn’t for them, or that opera singers can’t act — gave her one of the wildest ovations of the night.

At forty-two, DiDonato is probably the most in-demand lyric-coloratura mezzo in the world. Part of what has made her a star is her instinct for playing up, not down, to her audience. The marketing craze that infiltrated the opera industry years ago, and the more recent HD revolution, may have had a very positive effect on audience numbers. But they have also peddled a rather unpleasant subtext — namely, that opera is a frivolous, irrelevant art form that needs to have a compelling case made for it. At the 2011 OPERA NEWS Awards, a reporter enraged honoree Kiri Te Kanawa by asking her, “Do you think opera is elitist?” It’s this kind of manipulative, straitjacketed thinking that is starting to make Joyce DiDonato a little angry.

“I think there’s a real fallacy that if people don’t come to it, then it’s not interesting, or it’s not viable,” she said last May, when we met at the apartment she and her husband, opera conductor Leonardo Vordoni, have rented near Carnegie Hall. “I think, as a community, we need to quit apologizing for the fact that we’re a classical art form, and that we do opera. We’re giving opera a bad name, in a way, by the way we present ourselves — the way we sort of say, ‘Well, we know the plots aren’t very good, but we’ve got good costumes!’ Or ‘Well, we know it’s old-fashioned, and it’s long, but we have an exciting theater director doing it.’ Let’s get out there and tell people how great this art form is! We don’t sing with microphones, and what we do is extraordinary. Let’s be excited about it and quit apologizing for it.

“The other thing that’s driving me crazy is the notion that somehow, in the last five years, the opera community has finally discovered how to act. The style has changed — I’ll be the first to say that. If you go back and see an old Hitchcock movie, they were ridiculous in a way, in the way it’s stylized. But it’s of that time. Don’t tell me these people weren’t acting. They were doing a lot with the voice. So I think it’s really arrogant of me to start thinking we’ve reinvented the wheel. Our style is changing, and it’s exciting — I like the fact that I’m expected to go out there and be believable. But I don’t want to denigrate the generations that came before me.”

Such boldly expressed views may surprise those who have pegged DiDonato as the most relentlessly sunny of opera singers. (She sometimes seems, in interviews at least, a little too good to be true.) After all, DiDonato is one of the artists who have benefited most from exposure on the big and small screens. It was as Meg in the 2000 PBS telecast of Mark Adamo’s Little Women from Houston Grand Opera that she enjoyed her first taste of major success. Onstage and onscreen, she comes across as a natural teller of truths, someone with an easy, un-actressy integrity about her. She allows you room to feel what she’s thinking, to respond to the points in her performances, rather than shoving them at you. As a result, she has made one of the most successful transitions into the age of HD.

Like those who can’t quite believe that Kindle is going to spell the end of bookstores, DiDonato can’t quite believe that HD is that much of a threat to the live operagoing experience. “Ten years ago,” she says, “who could have ever predicted that opera would be live in movie theaters across the earth? The best analogy I can think of — the Super Bowl is the highest-watched television event, and yet it’s also the highest ticket-seller. People want to be in the sports stadiums — they want to be part of the group experience. You can’t replicate the roar of the crowd. You can’t replicate the hushed silence before the kickoff.

“Some people will say, ‘This opera actually translates better onscreen’ — for example, Capriccio at the Met. ButTurandot can never translate to the movie screen. Last night, I saw Priscilla, Queen of the Desert on Broadway. And my cheeks are still hurting, because I couldn’t stop smiling like a goofy kid. Even if you did that on HD, you could never get that thrill of seeing those first girls come down. It’s the gasp factor of those things you can see live — not to mention the sound.”

This resolve to make the best of the dramatic changes in the opera world is a key to DiDonato’s professional success and personal equipoise. Her close friend Lee Prinz, a manager at the New York firm Colbert Artists, recalls a concert she appeared in after being named one of the winners of the 1998 George London Competition. On a program alongside Jill Grove, Isabel Bayrakdarian and other up-and-coming singers, DiDonato sang “Deh, per questo,” fromIdomeneo, and “Things Change,” from Little Women. “She believed in that piece,” remembers Prinz. “It was something that spoke to her. She gave a little speech about ‘Things Change,’ and you could tell some people were like, ‘Yeah — O.K….’ For a long time she was ignored. Always fighting her way up probably made her a better artist. She worked her ass off to get what she’s got. She wants to be the better wife, the friendlier colleague, the better role model. There’s no complacency about her.”

In fact, DiDonato has much of the drive and tenacity, as well as the polished musicianship, of Beverly Sills and Renée Fleming — with one big difference: she doesn’t require that the audience love her. We are all too aware of how hard Fleming has worked to create her accomplished, star-pupil persona, just as we could sense when Sills, both on and offstage, was playing America’s Operatic Sweetheart just a little too hard. The image of likeability and charm that both women sweated to create comes to DiDonato far more naturally. She seems to have found an excellent balance between hard work and preparation and trusting her instincts onstage.

DiDonato remembers career-defining advice from Leonard Foglia, who directed her in Jake Heggie and Terrence McNally’s Dead Man Walking. “There’s no such thing as too big or too small,” Foglia told her. “There’s only true and false on the stage. Don’t show me everything you’re feeling. Let me decide, as the audience member, what you’re thinking. You don’t have to tell me.” It was direction like that, DiDonato says, that pressed her to question the depth and possibilities of what she was doing. “I’m constantly learning,” she says, “when I’m working with great, challenging people.”

She’s worked with a few of the other kind. “What will set me off more than anything is a director who has contempt for the art form,” she says. “I know too many people who love it and would pay to have the job. So if you don’t want this, go do television. Go do something else.” She refuses to name names, but when she appeared at the Met last season in the company premiere of Rossini’s Le Comte Ory, there were widespread rumors that she and Diana Damrau were stymied by the direction of Bartlett Sher. “As artists we need permission to fail,” she observes. “And if we don’t have that, we stifle our artistic creativity. Directors need the chance to fail. But if their journey of discovery leads them to a place that isn’t going to be successful, but it’s interesting, then maybe it will make their next venture mind-blowing — you know?”

One venture that she is eagerly anticipating is The Enchanted Island, the Met’s world-premiere Baroque pasticciothat opens on December 31, conducted by William Christie. DiDonato is known as one of opera’s leading Baroque specialists, a reputation that got a big boost when the first solo disc of her Virgin Classics contract, a collection of Handel mad scenes called Furore, earned her excellent reviews in 2009. “It’s my dream thing — the Baroque stuff I love, but a new creation,” she says. “What’s that Julie Taymor movie? Across the Universe, the pastiche done with all the Beatles tunes. So why not take great Baroque tunes and make a new story? It’s a total fantasy, taking The Tempestand A Midsummer Night’s Dream and mashing them together. The very fact that they sort of implode them on each other makes it very modern and very contemporary.” In The Enchanted Island, DiDonato plays Sycorax, a sorceress who loses, then regains, her powers. “She’s essentially a walking comatose, a decrepit,” laughs DiDonato, “and I can’t wait to see how bad they’ll make me look. Then, as she ends in full glory, with the color coming back to her, I hope they’ll make me look great. It’s a great team of creative people. Bill Christie is foaming at the mouth over the idea. He’s always wanted to do it, and now he finally is seeing it come to light.”

The foundation for DiDonato’s work ethic was established early on, when she was growing up in a large Catholic family in Prairie Village, Kansas. She was born Joyce Flaherty. (DiDonato is the name of her first husband; the marriage ended in divorce.) She had six brothers and sisters, and there was plenty of music at home. DiDonato’s father, a self-employed architect, constantly played the local classical station as he worked, but there was big-band music and jazz, too. There wasn’t a lot of money. “My parents really struggled,” she remembers. “It was a real — sometimes not even — paycheck-to-paycheck struggle.”

Within the family, DiDonato’s closest emotional connection was with her father. “I met somebody who explained that it’s not only partners you can be soul mates with,” she says. “I sort of felt that way with my dad — that we were soul mates.” She recalls her father as “a dreamer, the one saying, ‘Oh, I got a paycheck. Let’s take the kids out to dinner.'” Her pragmatic-minded mother was more inclined to point out that there was no canned food in the pantry. While her father encouraged her to embrace life’s larger possibilities, her mother was unable to join him in his enthusiasm, and it created a certain distance between her and her young daughter, who early on showed an eagerness to explore her talents. “I love that soaring idealism my father had,” she says. “And I try to cultivate some of that in me. I’m not at all interested in becoming bitter and jaded.”

Her father’s death, in 2006, was a shattering experience for her. Then, less than a year later, her mother died, while DiDonato was appearing at the Met in Il Barbiere di Siviglia. “We found a wonderful understanding between each other in the last few years,” says DiDonato. “I’m really grateful for that. At the end of the day, what makes me sad is I kind of feel like I didn’t know my mom. She was very closed and held a lot close to her. And I respect that. She absolutely did the best she could with what she knew and what she could do.”

DiDonato’s music education got a boost when she entered Bishop Miege High School, where she had what she terms “a great choral experience.” Also in high school, she played her first starring role, Veta Louise Simmons in Mary Chase’s Harvey. (“I always got the old parts,” she recalls. “I was a little zaftig in high school.”) She went on to attend Wichita State as a music-education major, but she soon realized she was spending much of her time performing — as Marcellina in Figaro, as Dorabella, as Hansel. She applied to one graduate program, at Philadelphia’s Academy of Vocal Arts, and was accepted, but her experience there was more noteworthy for the time she spent observing and soaking up information than for the time she spent onstage. “It was brutal,” she recalls. “Three years of the hardest sort of professional experience I’ve had. I remember being so smart, thinking, ‘They don’t know what they’re doing. They’re hard on us. They should be nurturing us.’ I had to grow a tough skin there. There is something to be said for that time span. The people there are twenty-two to twenty-eight, more or less. There’s weeding out that happens. And it needs to happen.”

The most significant thing she learned during her years at AVA was command of recitative. She arrived with a misconception that recits should be fast and furious; at AVA, she learned that “it’s all acting, all word choice, color — it’s clarity as opposed to speed. You learn so much about the characters through recit. And I hate it when they’re cut.” She also began learning how to sing coloratura with true expressivity. Her current voice teacher, Steve Smith, always reminds her, “Never sing the effect. You sing the intention, and the effect happens.” “The fast passagework,” DiDonato says, “if it has humor, pathos, all those things — then it actually has the chance for staying power.”

After a stint as an apprentice at Santa Fe Opera, she was accepted, in September 1996, into Houston Grand Opera’s Studio. She was twenty-seven. Her voice had ping and agility, but she couldn’t manage the passaggio with any finesse at all. Smith got her to rethink her highly muscled vocalism. “It was getting back to the speaking voice, so the cords could phonate without any pressure.” She appeared in three Houston world premieres — Michael Daugherty’s Jackie O, Adamo’s Little Women and Todd Machover’s Resurrection. By the time she left, at twenty-nine, she felt she was ready for an international career.

Her starring career soon unfolded in a making-up-for-lost-time manner, with debuts at La Scala (La Cenerentola, 2001), Bavarian Sate Opera (Cherubino, Figaro, 2002), Covent Garden (The Cunning Little Vixen, 2003), San Francisco Opera (Il Barbiere di Siviglia, 2003), the Met (Cherubino, 2005).

One of her most acclaimed roles fell outside her usual Rossini/Mozart beat — Sister Helen Prejean, the nun who attempts to help a convicted rapist/murderer reach a state of grace, in Heggie and McNally’s Dead Man Walking. She sang the role twice, in 2002 for her debut at New York City Opera and in 2011 at Houston Grand Opera. “I’ve never been for the death penalty,” she says. “However, I had a much more informed opinion at the end of the opera. People assume more black men are put on Death Row, but they’re not. It’s more or less half-and-half between white and black. However, murder victims are, in the 90th percentile, African–American and other minorities. It’s much more about whose life we value — not the criminals, but the victims. What DAs pursue, in economic and political terms, [the case of] a homeless black man who was killed in the street, as opposed to a twenty-five-year-old white woman?That’s the outrage. Whose life is more important? A black woman who’s a doctor? A black woman who’s on welfare? For me, the death penalty is the smallest part of the issue. Those other things are much bigger issues. And that’s why it’s a successful opera — it’s more about the human dimension.”

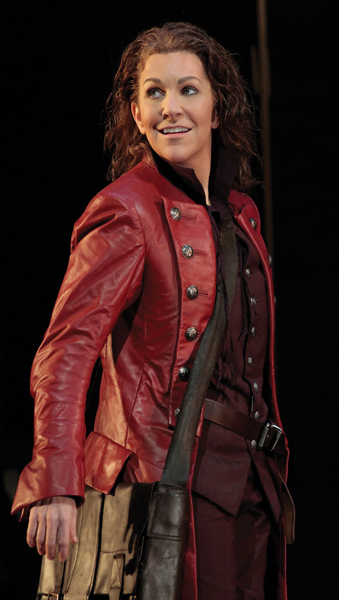

As Sister Helen in Dead Man Walking at Houston Grand Opera, 2011, with Philip Cutlip (Joe De Rocher) © Felix Sanchez 2011

These days, DiDonato and Vordoni maintain a home in Kansas City — not that they’re often in residence there. They met in 2003 at Pesaro’s Rossini Festival. In August 2006, while they were both performing in Santa Fe, they eloped to Las Vegas. As a nod to Vordoni, who grew up in Trieste, just two hours from Venice, they were married in a gondola. Their busy individual careers dictate that they must spend much of the time apart, but DiDonato claims, “We thrive being on our own. And you have to. I mean, it can’t be a black hole every time you get on that plane and go off to a strange city by yourself. I think, in a way, both of us look forward sometimes to being by ourselves a little bit, because we’re sometimes more productive when we’re apart. When we’re together, we just goof off a lot.”

Because Vordoni conducts much of the repertoire that his wife sings, it’s tempting to wonder if they would like to collaborate more than they do — to become the current generation’s Sutherland and Bonynge. “As a conductor, I’m a baby,” says Vordoni. “I have always wanted to have my career on my own terms, not because of my wife. Some people will say that I do have a career because of my wife. It’s an opinion, and you can’t stop it. I’m happy doing my own work, but I would never say, ‘Oh, I would never work with my wife.’ She makes all the preparation herself, and then I say something. You need to get in the groove first. But she’s my set of eyes and ears, and I’m hers. Funny story — we were in Houston. I always go to solve the problem first. I don’t just say, ‘You sound great.’ I was saying this and that, and she said, ‘Honey — good news first, please.’ I learned from that.”

Not long before our interview, DiDonato met with a class of voice majors at the Juilliard School. Given the plethora of lyric mezzos being turned out these days, I’m curious as to how many of the younger ones will be able to stay the course, as she has done — to put in the grueling work and yet give the appearance of complete, in-the-moment spontaneity. She thinks for a few seconds. “The training system is so good in the States,” she finally says. “It’s almosttoo good. There’s a very high standard of what’s expected, language-wise and technique-wise and all of that. However, what I see is the temptation for students to regurgitate what they’ve been told. They don’t know that they need to find out what’s unique about them, to do it their way. There needs to be a campaign put on not just perfect singing but expression. The technique has to be there — you have to have the ABC lined up. But that’s not the result you want.” For her, it all comes back to the ability to do the work. “There was no guarantee it was going to pay off,” she says. “But if there was a chance, I had to do the work. I wasn’t spoon-fed by anybody. No manager discovered me early on and walked me through the ropes. A lot of luck has come my way. But I really feel like, at the end of the day, I walked out there saying, ‘I have to make this happen.'”